Twin cyber operations conducted by state-sponsored Iranian threat actors demonstrate their continued focus on compiling detailed dossiers on Iranian citizens that could threaten the stability of the Islamic Republic, including dissidents, opposition forces, and ISIS supporters, and Kurdish natives.

Tracing the extensive espionage operations to two advanced Iranian cyber-groups Domestic Kitten (or APT-C-50) and Infy, cybersecurity firm Check Point revealed new and recent evidence of their ongoing activities that involve the use of a revamped malware toolset as well as tricking unwitting users into downloading malicious software under the guise of popular apps.

“Both groups have conducted long-running cyberattacks and intrusive surveillance campaigns which target both individuals’ mobile devices and personal computers,” Check Point researchers said in a new analysis. “The operators of these campaigns are clearly active, responsive and constantly seeking new attack vectors and techniques to ensure the longevity of their operations.”

Despite overlaps in the victims and the kind of information amassed, the two threat actors are considered to be independently operating from one another. But the “synergistic effect” created by using two different sets of attack vectors to strike the same targets cannot be overlooked, the researchers said.

Domestic Kitten Mimics a Tehran Restaurant App

Domestic Kitten, which has been active since 2016, has been known to target specific groups of individuals with malicious Android apps that collect sensitive information such as SMS messages, call logs, photos, videos, and location data on the device along with their voice recordings.

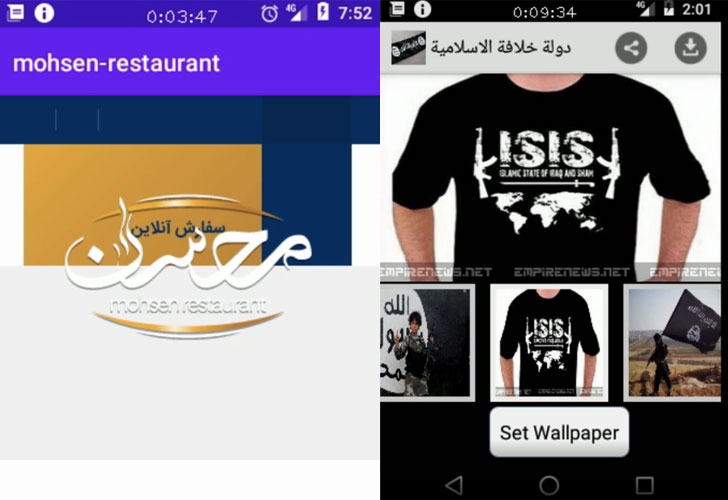

Spotting four active campaigns, the most recent of which began in November 2020 according to Check Point, the APT-C-50 actor has been found to leverage a wide variety of cover apps, counting VIPRE Mobile Security (a fake mobile security application), Exotic Flowers (a repackaged variant of a game available on Google Play), and Iranian Woman Ninja (a wallpaper app), to distribute a piece of malware called FurBall.

The latest November operation is no different, which takes advantage of a fake app for Mohsen Restaurant located in Tehran to achieve the same objective by luring victims into installing the app by multiple vectors — SMS messages with a link to download the malware, an Iranian blog that hosts the payload, and even shared via Telegram channels.

Prominent targets of the attack included 1,200 individuals located in Iran, the US, Great Britain, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Turkey, and Uzbekistan, the researchers said, with over 600 successful infections reported.

Once installed, FurBall grants itself wide permissions to execute the app every time automatically on device startup and proceeds to collect browser history, hardware information, files on the external SD card, and periodically exfiltrate videos, photos, and call records every 20 seconds.

It also monitors clipboard content, gains access to all notifications received by the device, and comes with capabilities to remotely execute commands issued from a command-and-control (C2) server to record audio, video, and phone calls.

Interestingly, FurBall appears to be based on a commercially available Spyware called KidLogger, implying the actors “either obtained the KidLogger source-code, or reverse-engineered a sample and stripped all extraneous parts, then added more capabilities.”

Infy Returns With New, Previously Unknown, Second-Stage Malware

First discovered in May 2016 by Palo Alto Networks, Infy’s (also called Prince of Persia) renewed activity in April 2020 marks a continuation of the group’s cyber operations that have targeted Iranian dissidents and diplomatic agencies across Europe for over a decade.

While their surveillance efforts took a beating in June 2016 following a takedown operation by Palo Alto Networks to sinkhole the group’s C2 infrastructure, Infy resurfaced in August 2017 with anti-takeover techniques alongside a new Windows info-stealer called Foudre.

The group is also suggested to have ties to the Telecommunication Company of Iran after researchers Claudio Guarnieri and Collin Anderson disclosed evidence in July 2016 that a subset of the C2 domains redirecting to the sinkhole was blocked by DNS tampering and HTTP filtering, thus preventing access to the sinkhole.

Then in 2018, Intezer Labs found a new version of the Foudre malware, called version 8, that also contained an “unknown binary” — now named Tonnerre by Check Point that’s used to expand on the capabilities of the former.

“It seems that following a long downtime, the Iranian cyber attackers were able to regroup, fix previous issues and dramatically reinforce their OPSEC activities as well as the technical proficiency and abilities of their tools,” the researchers said.

As many as three versions of Foudre (20-22) have been uncovered since April 2020, with the new variants downloading Tonnerre 11 as the next-stage payload.

The attack chain commences by sending phishing emails containing lure documents written in Persian, that when closed, runs a malicious macro that drops and executes the Foudre backdoor, which then connects to the C2 server to download the Tonnerre implant.

Besides executing commands from the C2 server, recording sounds, and capturing screenshots, what makes Tonnerre stand out is its use of two sets of C2 servers — one to receive commands and download updates using HTTP and a second server to which the stolen data is exfiltrated via FTP.

At 56MB, Tonnerre’s unusual size is also likely to work in its favor and evade detection as many vendors ignore large files during malware scans, the researchers noted.

However, unlike Domestic Kitten, only a few dozen victims were found to be targeted in this attack, including those from Iraq, Azerbaijan, the U.K., Russia, Romania, Germany, Canada, Turkey, the U.S., Netherlands, and Sweden.

“The operators of these Iranian cyber espionage campaigns seem to be completely unaffected by any counter-activities done by others, even though they were revealed and even stopped in the past — they simply don’t stop,” said Yaniv Balmas, head of cyber research at Check Point.

“These campaign operators simply learn from the past, modify their tactics, and go on to wait for a while for the storm to pass to only go at it again. Furthermore, it’s worthy to note the sheer amount of resources the Iranian regime is willing to spend on exerting their control.”