Content warning: suicide and mental illness

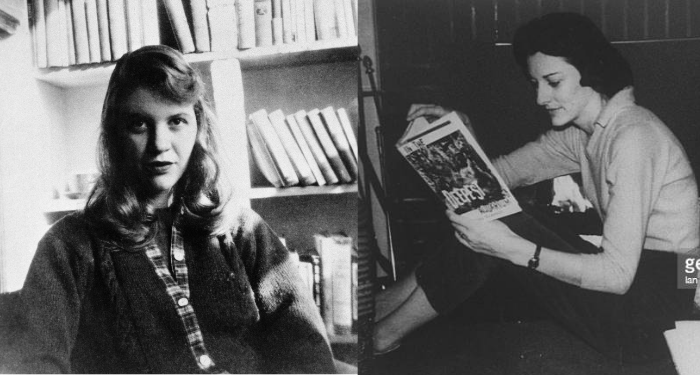

Sylvia Plath has come to mean a kind of shorthand, both culturally and in literary circles. You could say the same about Anne Sexton, although much less so, at least in my opinion. Plath has come to be a symbol of an angsty, depressed teen girl who takes herself too seriously and listens to a lot of Tori Amos or Portishead. If you let slip in an MFA class that your favorite writers are Plath and Sexton, I can only imagine the kind of judgment you might meet or the glances that would be exchanged among classmates. Plath has become a sort of cultural joke. No matter that she could easily write fiction, poetry, and children’s books — and could illustrate them as well — her talent falls by the wayside. There was even a tactless, disgusting photo shoot by Vice years ago that pictured several suicides of women writers, including Plath’s. Plath and Sexton seem to lack a certain kind of literary gravitas that is afforded to other poets, and I can’t help but think it is because of the cultural components to all of this.

Do we make the same assumptions about someone — especially a cis man — reading Styron? Or Hemingway? The assumptions we may make about a man reading Hemingway would be the flannel-shirt wearing, rugged individualist kind, not so much the suicidal and depressed kind. Even David Foster Wallace, whose struggles with depression were many and well-known, escapes these jokes or cultural stereotypes. (He’s also had multiple #MeToo accounts about him, but that doesn’t seem to affect his reputation, either). People who tote around Infinite Jest are simply seen as pretentious, absent any inferences about their mental health or moods. If you’re a DFW fan, you’re usually seen as someone Very Literary, not someone Going Through a Wallace Phase.

Let’s also not ignore the fact that poets of color have not gotten and still do not get the same recognition as many white poets. They have not been as universalized as white poets in the way that results in these associations, for better or worse — which is why all the poets mentioned in this post are white. (And there’s whole other discussion to be had about race and the medical establishment’s recognition of depression/mental health issues.)

Facing My Own Bias

I recently realized that I myself had internalized this sexism when I told someone I was reading Three-Martini Afternoons at the Ritz: The Rebellion of Sylvia Plath and Anne Sexton by Gail Crowther (out April 20), along with the 1000+ page book Red Comet: The Short Life and Blazing Art of Sylvia Plath by Heather Clark. I made a joke, something like, “Clearly I’ve never grown out of my Plath angsty phase.” And then I wondered why I was making excuses for reading about two trailblazing writers — one of whom won a Pulitzer Prize — who are very much still relevant today. Because somewhere along the line, I internalized the stereotypes. I fed into the tropes.

Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, and Me

Yes, I first read Plath and Sexton as a moody teenager. Sexton scared me; her raw and unfiltered honesty was a sharp contrast to Plath, I felt, though I couldn’t have explained it at the time. She felt more mercurial to me, and her poetry a little less accessible, though I read it and mulled over it just the same.

As the years went by, I kept reading and rereading their work, and finding more things to appreciate in it. I read biographies and journals, and I realized just how ahead of their time they were in many ways. This was the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s – they were working writers, mothers, and wives, with many people judging them for focusing on their writing, instead of giving it all up to be mothers and wives only (although Plath was very much traditional in many ways). They were outspoken, sexual women at times when this was frowned upon.

And yet, even though I knew their writing was exemplary, I also knew not to bring them up in certain academic conversations and situations. I could see the amusement in people’s eyes on the few occasions I admitted my admiration for their writing. These women were simply Not Literary — or Not the Right Kind of Literary, anyway.

Their writing was brash and honest. They wrote about pregnancy, miscarriage, suicide, life, family, and sex. Their writing was revolutionary, especially then. Yet even now, people — including writing teachers and critics (maybe especially these people) — dismiss it as “confessional.”

Ah, that dreaded word that is somehow mostly only applied to women writers who dare tell the truths of their lives. Men are almost never deemed “confessional” writers. Confessional is messy. Confessional is “too much.” Calling writing “confessional” implies that the writing is not crafted diligently, that it is meant for personal journals and not literary publication. There is an unhinged emotionality tethered to “confessional.” But this is only if you’re not a man. Conroy, Steinbeck, Lowell, Nabokov, Vidal — they’re never “confessional,” only daring and forthright.

These women also treated writing as their job, not simply a romanticized calling – Sexton demanded to be paid what she felt she was worth, especially when she knew men were paid more for the same job she was being asked to do. Plath had a keen eye for the market, took notes on what stories and articles sold in magazines, and realized at one point that writing about mental health issues sold. Plath was unbelievably critical and rigorous with herself and her writing, and Sexton, despite rejecting formal schooling, self-educated to the point where she became a professor at Boston University. These women were brilliant scholars who also realized the chaos their mental illnesses wreaked on their lives, and they hated it.

Understanding Their Lives Moving Forward

Reading about the suicides of Plath and Sexton now, as a 40-year-old mother, is very different than my reading of them as a teenager. In Clark’s book, she painstakingly researched Plath’s last weeks, despite the fact that Hughes claimed her last journal was “lost.” What she found is alternately horrifying and devastating: Plath was clearly not well and struggling — and well aware of how she was struggling. She was given a medication that went by a different name overseas that she had a very bad reaction to in the States after her first suicide attempt. She was on a cocktail of amphetamines, downers, cold medicine, and antidepressants. There was an impending hospitalization. Her doctor considered hospitalizing her earlier, but decided against it. And on and on. Sexton had become an alcoholic, drinking very heavily, all the time. Her therapist abandoned her. She abruptly stopped taking her medication. She pushed many people away, isolating herself as her physical and mental health worsened exponentially.

There is nothing romantic or funny about these deaths, despite the dark jokes or stereotypes. These two writers made an impact on the literary world in the short time they had, but what could they have done had they lived even longer?

Reframing Plath and Sexton

So where do we go from here? How do we divorce these writers from the stereotypes? Is that even possible at this point? I’m not sure.

I hope to see their writing and contributions be recognized more by those in the Literary World, instead of being brushed off as the territory of moody teen girls. As Crowther notes in her book, too often, people come to understand these women and their writing backwards, from their deaths. Their deaths color the rest of their lives and work, when that should not be the case at all. Their lives and work are bigger than the circumstances of their deaths. Bigger than their mental health struggles. In essence, that is what Clark’s book on Plath does — it delves into her life: her goals, her relationships, her unrelenting appetite for work and writing and the love for her children — illustrating that her death should not be the event that colors everything else. I’d love to see a book taking on Sexton’s life and work in this kind of detail.

In the meantime, I’ll be over here rereading their poetry and writing, and not making any excuses for it.