Dealing with David Cameron’s multiple texts, WhatsApp messages, emails and phone calls “did not take up a very significant part” of the Treasury’s time, Chancellor Rishi Sunak has told MPs investigating the Greensill lobbying scandal.

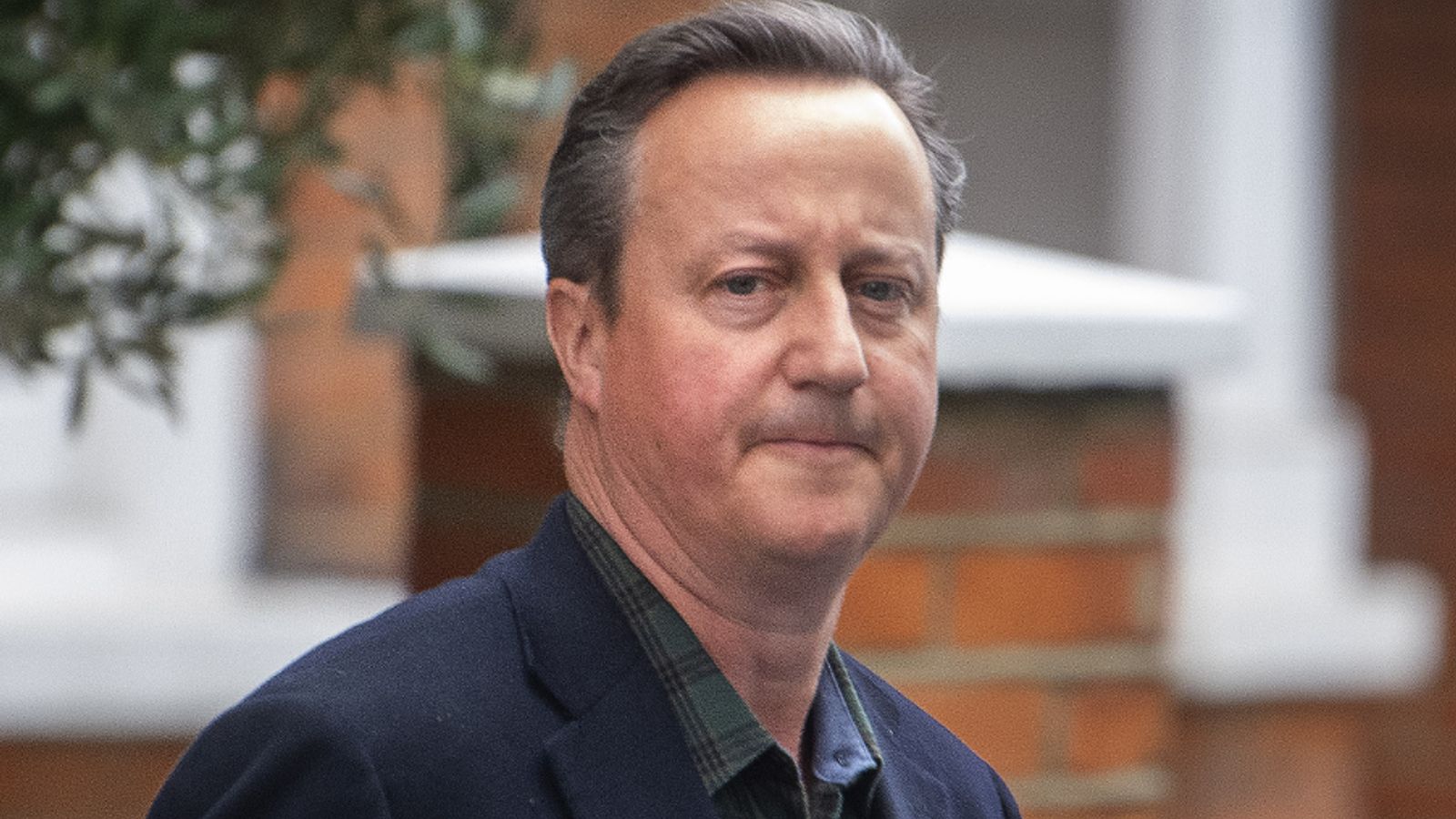

Earlier this year, ex-prime minister Mr Cameron was revealed to have bombarded government ministers and officials – as well as the Bank of England – with messages in a bid to win a now-collapsed finance firm access to government-backed COVID support schemes.

But, in a letter to MPs on the House of Commons Treasury committee, Mr Sunak dismissed the impact that Mr Cameron‘s actions had on his department’s decisions over Greensill Capital.

The chancellor wrote to the committee following the release of their report on the lobbying scandal in July.

In his response to the committee, Mr Sunak said: “The report expresses doubt that Mr Cameron’s lobbying did not result in the Treasury treating Greensill differently.

“On this I can only reiterate the evidence we have previously given to the committee.

“Greensill and supply chain finance did not take up a very significant part of my time, nor of [Treasury second permanent secretary] Charles Roxburgh’s, nor of the department’s overall, particularly compared with other COVID interventions.

“In line with the committee’s report, it was right to listen to Greensill’s initial proposal, which we promptly rejected.

“Given the acute financing needs of SMEs at the time, it was also right to invest a small proportion of time and resource in exploring the option of an industry-wide solution for supply chain finance.”

The chancellor also told MPs of his belief that the Treasury “acted entirely appropriately in relation to Greensill” and that he was “proud” of his department’s response to the COVID crisis.

Among Mr Cameron’s contacts with government ministers and officials were 14 text messages to the Treasury’s most senior civil servant Tom Scholar; eight WhatsApp messages and two phone calls to Mr Sunak; six texts, one call and one email to Treasury ministers John Glen and Jesse Norman; and two WhatsApp messages to an aide of Mr Sunak.

The Treasury committee previously published a vast number of Mr Cameron’s contacts, but some of Mr Scholar’s replies to the former prime minister were unable to be found when subsequently requested under Freedom of Information laws.

The Treasury said this was due to Mr Scholar’s mobile phone being reset after the device was automatically locked when an incorrect password was entered several times.

It was later revealed the Treasury had wiped all data from more than 100 government-issued mobile phones in 2020 because their users entered the wrong pin.

In its report on the Greensill scandal, the Treasury committee urged the government to review “its policies and use of information technology to prevent the complete deletion of government records by the misremembering of a password to a phone”.

But, in his response to the MPs’ report, Mr Sunak suggested his department would not be making any changes.

“While we accept that, in exceptional circumstances, this security feature could potentially result in the loss of information that may not have been transferred to the departmental record, in the vast majority of cases, all the substantive information held on the device will also be held on Treasury systems,” he wrote.

“Given that the aim of the Treasury’s policy is to ensure that all data is protected in circumstances where a device is either lost or stolen (where it could potentially be in the possession of malign actors), we consider that the balance of risk falls decidedly in favour of retaining the security feature in order to prevent unauthorised access to Treasury information or data, which is often particularly high-profile and sensitive.”