This article contains spoilers for Dune. Both of them.

For miles stretching as far as the eye can see, oceans of sand slumber beneath two moons. In the distance, a pair of figures, a mother and son, cross this vast chasm of dunes on their quest to find those blue-eyed devils they call the Fremen. Yet as Paul Atreides and Lady Jessica move through the harsh landscape, they realize a creature—a monstrous Sandworm the size of a skyscraper—is headed straight for them.

Am I describing Denis Villeneuve’s new adaptation of Frank Herbert’s literary masterpiece, Dune, or David Lynch’s previous 1984 stab at the same material? Honestly, in moments like these, they’re surprisingly similar: intended epics made by filmmakers committed to doing justice to what many believe is the finest science fiction novel ever written. And yet, more often than not, the differences are as colossal as the desert of Arrakis itself.

Largely hated and dismissed in its time by critics and general audiences—even its director isn’t too fond of the finished product, taking his name off extended television cuts—Lynch’s Dune has developed a cult classic status in recent years. Indeed, you’ve likely already seen spicy hot takes on social media where folks declare the once reviled adaptation produced by Dino De Laurentiis to be superior to the modern Hollywood spectacle helmed by the Oscar-winning auteur behind Arrival and Blade Runner 2049.

Well, we’re not here to tell you which you should prefer (although we have a clear preference). Rather the two films offer a fascinating case study in how the different choices made by different filmmakers, even while working toward the same goal and with the same source material, can produce vastly different results. Below are the variances, great and small, that when added together create viscerally diverging interpretations of a tale about a boy, a desert, and the spice melange….

How the Dune Saga is Framed

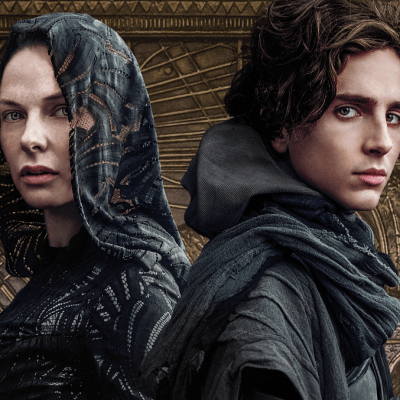

The biggest difference between the two films is that Villeneuve’s movie is not an adaptation of the whole 1965 novel. In fact, it only covers about half the book, ending at a midway point where Paul Atreides (Timothée Chalamet) and his mother, the Lady Jessica (Rebecca Ferguson), have been cautiously accepted by a Fremen leader after Paul slew one of their men in holy combat.

All the elements of Paul being fully embraced by the Fremen, leading them into a coordinated uprising against House Harkonnen, his fateful meeting with the Padishah Emperor, and even earning the name Muad’Dib have been left for a second movie. As such, we won’t be comparing the elements left to a second film beyond this point. However, the choice by Villeneuve to cut Dune into two movies already appears to be a prudent one by simple comparison with Lynch’s movie.

While the Lynch film has its fans, even the most ardent admirer will concede the back half of the picture, particularly the third act, is a dizzying narrative cluster where one damn thing happens after another. The pacing and storytelling structure is so top-heavy and unwieldy that it makes the plot impenetrable to most newcomers. It’s one of the key reasons Gene Siskel and Robert Ebert famously declared Dune to be among the worst movies of 1984, with Siskel calling it an “unintelligible gross out.”

Beyond not attempting to squeeze Herbert’s whole sprawling yarn into two or even three hours, another fascinating choice made by Villeneuve’s Dune is how it jettisons the framing device of the novel, where many of the chapters’ events are foreshadowed with an excerpt from a history text written by the character Princess Irulan in the distant future. While Herbert frames the events of Dune as significant historical events among the ruling patrician classes of his intergalactic “Imperium,” with a literal princess recording the events for posterity, Villeneuve’s Dune begins with Zendaya’s Fremen character Chani as the narrator.

Immediately, we are asked to consider the events of Dune not through the gaze of the wealthy and elite that history so often memorializes, but from the vantage of the oppressed and forgotten, such as the Fremen freedom fighters who have already drawn blood from the villainous House Harkonnen—the villains of the piece exploiting Arrakis when the movie(s) begin. Since this is ultimately a story about how the powerful exploit and manipulate large populations of people for natural resources, viewing it from the perspective of those who already have the boot on their face gives an instantly more visceral feeling to the material. It also causes the viewer to question the intentions of the film’s protagonists, the more kind-hearted Atreides household who is still coming to Arrakis as stewards and rulers of the colonized, indigenous population.

Lynch, by contrast, introduces his version of this universe with an exposition dump. It’s actually accurate to the novel to have the exposition be narrated by Princess Irulan (Virginia Madsen), but the dialogue is clunky and heavy-handed, likely due to the awkward close-up of Madsen in front of a starry sky (but really an obvious blue screen), the result of a note from the producers after test screenings. These were the same notes that led to the disastrous postproduction choice of having nearly every character’s inner-monologue narrated by the actors in scenes where it was never warranted.

It’s also worth noting how after Madsen explains the general setup of Dune (1984) in the movie’s prologue the film then transitions to Kaitain—a planet never seen in the original Dune novel—to then introduce the Padishah Emperor Shaddam IV (José Ferrer) and his daughter Irulan conspiring with a fish-person. If you haven’t read Dune Messiah (1969), Herbert’s second novel, you would have no foreknowledge that the Spacing Guild’s navigators have mutated into fish creatures by sucking on too much spice melange. And if you missed a dropped line in Madsen’s exposition dump a minute earlier about this fact (which many did), this scene is totally incomprehensible sci-fi gibberish, and a fairly awkward way to introduce us to the narrative.

It’s for this reason that we again give credit to the elegance of Villeneuve’s approach which after a voiceover prologue that was light on jargon, Dune (2021) then gradually introduces you to its sci-fi concepts, just as our protagonist Paul Atreides becomes acquainted with them. It’s actually how Herbert did it in the novel, and makes for a better approach than throwing viewers headfirst into the deep end.

Caladan, House Atreides, and Paul

Both films make similar choices in how they depict Caladan as a landscape and birthplace for Paul. If Arrakis, the desert planet where we spend most of the story, is horrifying for its blazing sun and merciless dry heat, then it is apt to highlight the wetness and greenery of Caladan. Each film depicts Caladan as perpetually overcast with gray clouds filled with moisture.

And it is there we meet Paul and the people who raised him. Both Chalamet and Kyle MacLachlan do solid work as the young boy hero, although MacLachlan’s interpretation more heavily emphasizes said heroism. Produced one year after Return of the Jedi, Lynch’s Dune more openly presents Paul as a Luke Skywalker type with a gung-ho spirit that’s ready for an adventure. He has a pretty lighthearted relationship with all of his father’s men, including Gurney Halleck (Patrick Stewart), Thufir Hawat (Freddie Jones), and Duncan Idaho (Richard Jordan).

Chalamet’s Paul is more visibly brooding and introverted than MacLachlan’s. While he is anxious to begin his life on Arrakis, and can still bust Josh Brolin’s Gurney Halleck’s chops, he also wears his responsibility more heavily. It is worth considering if this also has something to do with the direction of the characters’ journey. Whereas Dune (1984) feels like a traditional hero’s journey (more on that below), Villeneuve’s variation embraces early on the faint tragic quality of the literary Paul, which will presumably be heightened if and when Villeneuve makes any sequels.

Similarly, there is a stark funereal quality to how Villeneuve depicts the Atreides culture on Caladan. With most characters wearing blacks and grays, these appear to be an austere people. It also led to bold choices in the Dune (2021) production design with Paul’s home world being filled with stone masonry and heavy wooden furniture. It underscores the feudal quality of this society, and the long history of Paul’s family. By contrast, the technology and look of House Atreides in Dune (1984) is more traditional 1980s sci-fi movie aesthetics. With that said, the costuming is quite interesting in Lynch’s film, with House Atreides resembling a kind of 19th century European militaristic society worthy of Prussia or the Ottoman Empire on their homeworld, and then looking more like a late 20th century Middle Eastern dictatorship when the Atreides arrive on Arrakis.

The actual Atreides family and their courtiers are also notably different. Both Jurgen Prochnow and Oscar Isaac bring a bearded weariness to Duke Leto Atreides, however Rebecca Ferguson’s Lady Jessica enjoys a much more domineering and authoritative quality over her household than Francesca Annis’ version of the same character. The Lady Jessica of Dune (1984), like many of the female characters in that version, is often a passive observer of events instead of a major participant. It’s an odd choice since Jessica is with Paul for his entire journey in the first novel, which is perhaps why the first time we see Paul not dreaming in Dune (2021), he’s being instructed by his mother first in the witchy ways of the Bene Gesserit, establishing their unusual mother/son dynamic before we see him interact with anyone else.

Villeneuve also does superb work making the Areides retainers more individually interesting. This is most apparent in the case of Duncan Idaho, who is supposed to be Paul’s surrogate big brother and uber cool role model. Despite being played by a great character actor in the ’84 version, Duncan Idaho is almost a nonentity in the movie and may have been a casualty of heavy reedits in post-production. Meanwhile Villeneuve cast the most swaggering superhero actor of the last few years with Jason Momoa, who has charisma as hot as any desert. His Duncan is so larger than life, he actually becomes the movie’s one source of typical blockbuster fun—making his death mean more later in the picture.

House Harkonnen and the Baron

Here is where the differences between both versions of Dune start becoming eye-popping. And for many, the loss of sight might’ve been preferable to how the Baron Vladimir Harkonnen is depicted by actor Kenneth McMillan and the legion of prosthetics applied to him by Lynch’s makeup artists. The character of Baron Harkonnen is described as a grotesque, obese, and lascivious old man in Herbert’s novel, and Lynch revels in that image and then amplifies its implied ugliness.

In addition to emphasizing the character’s size by putting him in a form-fitting suit that looks like an overgrown diaper, Lynch also gives the character repulsive lesions on his face, as if he had bad acne as a child and let it fester into a veritable parasite. The character’s repellent lustfulness for young boys in the book is likewise heightened by Lynch, who makes a big set-piece out of the Baron seemingly raping a young male slave while holding court with his nephews, and then visibly killing the boy by bleeding him to death—it was a Lynchian flourish that the Baron would force everyone under his control (including inexplicably himself?) to have their nipples turned into glorified wine corks, which when pulled would bleed the victim to death in an instant.

Yet for all this grossness, Lynch and McMillian’s interpretation of the villain is so luridly over-the-top and cartoonish that he ultimately resembles a disgusting clown instead of an evil mastermind—a character who spends more time cackling about his vileness than displaying any sort of cold Machiavellian ruthlessness capable of slaughtering an entire family.

Which could explain Villeneuve’s determination to distance himself from that kind of villainy. Stellan Skarsgård’s Baron Harkonnen is still wildly overweight and reliant on anti-gravity technology to move his girth from Point A to Point B. However, his immensity is often obscured or merely hinted at, with Skarsgård underplaying the character as restrained and calculating in extreme close-up. Kind of like a latter day Brando, this Baron is quiet but still inexplicably larger than life, looming over anyone else in the scene.

Villeneuve and company also perhaps wisely removed the homophobic and pedophilic elements of the character, which are present in the novel. In fact, the apple of the Baron’s eye, his own golden boy nephew Feyd-Rautha (memorably played by rock star Sting in the 1984 movie) is totally removed for Villeneuve’s first volume. Instead the filmmaker basks in the oppressive gloom of the Baron’s world, seemingly evoking H.R. Giger in the menacing production design. Giger famously was supposed to design the Baron’s world in Alejandro Jodorowsky’s Dune movie which never got made. So Giger instead designed the title creature and alien spacecraft in Ridley Scott’s Alien (1979).

Frankly, there is no universe where Villeneuve’s version of the Baron and his Giedi Prime is not superior to Lynch’s, although I admittedly like the green fire pits Lynch uses in one matte painting establishing shot.

The Bene Gesserit, Mentats, and World Building

But if the Baron is the first significantly eye-catching distinction between the two Dune movies, it is also just one of many choices that distinguish the approaches between Villeneuve and Lynch’s interpretations. And like the Baron, time and again the impulses seem to be divided between regal restraint and an almost comical grandiosity.

Some of this is due simply to the difference of special effects, which after nearly 40 years of advancement seem almost unfair to compare. For instance, the forcefield shields that the richest members of House Atreides and Harkonnen use look much better in 2021, as a translucent second skin as opposed to an optical blob inserted on top of the film print. But that is partially due to the differences in technology, as well as Villeneuve having a major Hollywood budget, and Lynch being forced to deal with the relatively more limited means that comes with working outside the then-big six studios. (With that said, it was a cunning instinct by Villeneuve to have the shields glow blue when they deflect an object and red when they don’t, making it easier to signal the difference to uninitiated viewers about how they’re supposed to work.)

Perhaps the best way to appreciate these aesthetics is to consider how the weirdness of Herbert’s universe is built and developed between the two films. In Lynch’s Dune, everything is broadly drawn to almost caricature levels. Mentats, the people raised to be essentially human supercomputers since birth, have wild hair and makeup designs which make them look like glam metal rockers who developed a bad case of syphilis. Whereas Villeneuve gives Stephen McKinley Henderson the faintest of makeup markings on his lips and an occasional digital eye effect to suggest an otherworldliness. Henderson also is asked to play a mentat as a wise, grandfatherly character instead of like a broad Dickensian portrait of snobbery.

In the same vein, the Bene Gesserit appears radically different even while functioning the same in the story. In Lynch’s film, most of the high-ranking members lean into the visual space oddity vibe of Baron Harkonnen. Silvana Mangano’s Reverend Mother Mohiam particularly looks designed to suggest an androgynous, asexual aesthetic with the dark costume drawing attention to her starkly bald head. Even the eyebrows are shaved. Lady Jessica also adopts this look after becoming the Reverend Mother for the Fremen tribe on Arrakis. And yet, there is something regressively antiquated about this. It seems to suggest that in order to gain power, Jessica must give up her traditional femininity, as characterized by the loss of her hair. Lynch also seems to link sexuality to this trade, hence his greater focus on Jessica’s concubine status with Duke Leto and (like the book) having her rely on her sensuality as much as “the Voice” to manipulate and escape the Baron’s men after she and Paul have been captured.

Read more

Villeneuve’s Bene Gesserit, by contrast, also lean into the weird, metaphysical side of Herbert’s world-building. However, rather than relying on physical appearances or sexuality (or a lack thereof), Dune (2021) emphasizes these characters’ witchiness as understood by the folk horror tradition out of European culture. When the Reverend Mother Mohiam (Charlotte Rampling) arrives on Caladan in the new adaptation, she and her former pupil, Jessica, are clad in flowing black cloaks and headdresses which recall a faint collective memory of how the fictional concept of a witch has been drawn for centuries. Even Hans Zimmer’s score in these scenes resembles the chanting heard at the end of Robert Eggers’ The Witch (2016).

And when Ferguson’s Lady Jessica uses the Voice, there isn’t anything seductive or suggestive about it. It is, in fact, quite creepy how her voice develops a scratchy demonic quality, as if her vocal cords are being stretched along a violin’s string. And when she uses it to escape from the Harkonnens’ grasp, it is with the harshness of C.S. Lewis’ White Witch that she commands her prey to “kill him… Give me the knife.”

All of which provides the world in Villeneuve’s Dune an ancient, foreboding quality, as if it’s existed for millennia with eons of history and lore we’ll never know. Lynch’s world conversely seems to only exist in the frame of the story it is currently telling; it’s operatic and melodramatic, but only makes as much sense in the moment it’s occurring. Don’t think too hard about why the Baron created an instant-kill switch on his own body, or how anyone can take these Mentats seriously. It’s meant to be a big and gaudy “sci-fi movie,” okay?

The Fremen and Their Messiah

It is somewhat ironic that the culture which is vital to the narrative of Herbert’s literary Dune has yet to be fully explored on the big screen. In the case of Villeneuve, he left that for a potential “Part Two,” which may or may not ever come. And in the case of Lynch, the Fremen were largely left on the cutting room floor or out of the screenplay since in the theatrical, 130-minute version of the movie, they don’t even really enter the plot until the 90-minute mark.

Nonetheless, what little we see of both movies’ Fremen indicates, again, a different set of priorities. In both films, the Fremen’s presence is mostly teased out by Paul’s visions and the character of Dr. Liet Kynes. In Lynch’s film, as well as the novel, Dr. Kynes is an old male retainer from the imperial court who has gone native after living on Arrakis for 20 years. He is ably played by Max von Sydow in that movie, but due to the rushed narrative of the film’s second half, he more or less vanishes from the picture after being condemned to death by the Baron. Sharon Duncan-Brewster’s Dr. Kynes has been gender-flipped, and is also played by a Black woman, yet gets to develop more of the character’s inherent authority and compassion from the book.

We see Duncan-Brewster’s Kynes struggle with ignoring the plight of House Atreides and then eventually agree to aid young Paul and his mother after they’ve become exiles in the desert. Her death also has more weight than how Kynes dies off-screen in Lynch’s film or in even the book, with this Kynes summoning a Sandworm to devour her and her killers. The thoughtfulness of this revision speaks to how the Fremen culture has been subtly reimagined overall in the 2021 film.

In terms of appearance, the characters are more multicultural as opposed to the seemingly Caucasian descriptions of the Fremen in the book, and the outright whiteness of the whole cast in the 1984 movie. But then that’s also a movie that casts a white man even in the one definitely non-white role from the book, Dr. Yeuh. In addition to the first significant Fremen characters in the 2021 film being played by actors of various backgrounds, including Javier Bardem, Zendaya, and Babs Olusanmokun, the new Fremen tribe feels more developed and foreign from Paul and Jessica’s understanding of the world.

Villeneuve embraces the Middle Eastern influences on Herbert’s vision for the Fremen. While his movie noticeably avoids the word “jihad,” which is used freely by the Fremen and Paul in both the book and 1984 movie, more Arab-inspired words make it into the script, as do hints of an Islamic-inspired religious culture on Arrakis when we first arrive in the city of Arrakeen and witness the daily prayers.

Most of all, however, the Fremen characters have much more agency in the 2021 film. While we’ve only seen a hint of their culture teased, there is a greater deal of reluctance from Stilgar and his fellow Fremen to actually believe that Paul is a messianic figure. Jamis even challenges Paul to a duel, which is absent in the 1984 movie. Zendaya’s Chani is likewise warier of this Paul Atreides kid. This is a noticeable departure from Sean Young’s Chani, who like many of the female parts in the original adaptation is underwritten and vacant—waiting to be swept off her feet.

But that description could apply to the Fremen themselves, who eagerly accept Paul’s leadership in 1984, including via tutelage in a vocal sonic weapon Lynch invented for his movie. And at the end of the film, they’re more or less justified for idolatry since the denouement reveals Paul to truly be a magical messiah figure, even bringing rain to the desert.

While we haven’t yet seen how Chalamet’s Paul will win the Fremen over, we imagine it will have a lot more room to breathe—and it won’t need to rely on feats of Christlike miracle either.

Whatever Kind of Spice You Like

It’s probably clear if you’ve read this far that I lean in favor of the 2021 film more than its ’84 predecessor. Nonetheless, there are charms to be found in both films. Lynch’s movie is the product of a B-production with A-picture aspirations being greenlit in the wake of Star Wars. The grandness of Lynch’s ideas and images colliding with the limitations of his era creates an endearing, kitschy juxtaposition for many. Plus, there is something comfortingly nostalgic about ‘80s special effects and that wonderful theme by Toto, isn’t there?

Villeneuve has more advanced technology and the backing of a bigger budget to realize his own “visions,” and he had the ability to learn from Lynch’s mistakes and not attempt to squeeze an overabundance of story into a conventional running time. There is a bombast to his gargantuan IMAX photography as well, but there’s also a subtlety that some will probably find pretentious. To return to the music, it can be as telling as the fact that instead of going for a pop rock band to score the main theme, Villeneuve tapped Hans Zimmer to “invent” new instruments and sounds for the Fremen culture. One approach will likely appeal to you more than the other. So long as the spice still flows, either way you get to Arrakis is worth a go. No?

Dune (2021) is in theaters, and both movies are on HBO Max.