Banking apps from Brazil are being targeted by a more elusive and stealthier version of an Android remote access trojan (RAT) that’s capable of carrying out financial fraud attacks by stealing two-factor authentication (2FA) codes and initiating rogue transactions from infected devices to transfer money from victims’ accounts to an account operated by the threat actor.

IBM X-Force dubbed the revamped banking malware BrazKing, a previous version of which was referred to as PixStealer by Check Point Research. The mobile RAT was first seen around November 2018, according to ThreatFabric.

“It turns out that its developers have been working on making the malware more agile than before, moving its core overlay mechanism to pull fake overlay screens from the command-and-control (C2) server in real-time,” IBM X-Force researcher Shahar Tavor noted in a technical deep dive published last week. “The malware […] allows the attacker to log keystrokes, extract the password, take over, initiate a transaction, and grab other transaction authorization details to complete it.”

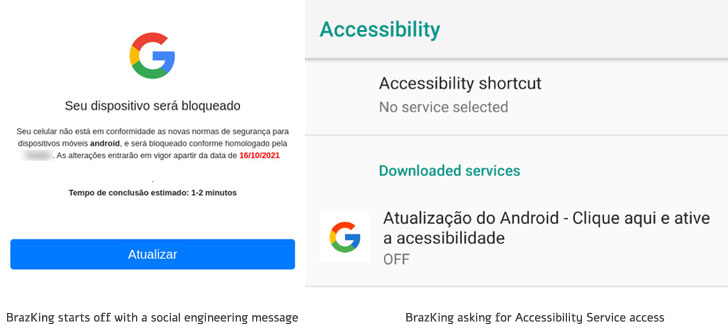

The infection routine kicks off with a social engineering message that includes a link to an HTTPS website that warns prospective victims about security issues in their devices, while prompting an option to update the operating system to the latest version. However, for the attacks to succeed, users will have to explicitly enable a setting to install apps from unknown sources.

BrazKing, like its predecessor, abuses accessibility permissions to perform overlay attacks on banking apps, but instead of retrieving a fake screen from a hardcoded URL and present it on top of the legitimate app, the process is now conducted on the server-side so that the list of targeted apps can be modified without making changes to the malware itself.

“The detection of which app is being opened is now done server side, and the malware regularly sends on-screen content to the C2. Credential grabbing is then activated from the C2 server, and not by an automatic command from the malware,” Tavor said.

Banking trojans like BrazKing are particularly insidious in that after installation they require only a single action from the victim, i.e., enabling Android’s Accessibility Service, to fully unleash their malicious functionalities. Armed with the necessary permissions, the malware gathers intel from the infected machine, including reading SMS messages, capturing keystrokes, and accessing contact lists.

“Accessibility Service is long known to be the Achilles’ heel of the Android operating system,” ESET researcher Lukas Stefanko said last year.

On top of that, the malware also takes several steps to try to protect itself once it has been installed to avoid detection and removal. BrazKing is designed to monitor users when they are launching an antivirus solution or opening the app’s uninstall screen, and if so, swiftly return them to the home screen before any action can be taken.

“Should the user attempt to restore the device to manufactory settings, BrazKing would quickly tap the ‘Back’ and ‘Home’ buttons faster than a human could, preventing them from removing the malware in that manner,” Tavor explained.

The ultimate goal of the malware is to allow the adversary to interact with running apps on the device, keep tabs on the apps the users are viewing at any given point of time, record keystrokes entered in banking apps, and display fraudulent overlay screens to siphon the payment card’s PIN numbers and 2FA codes, and eventually perform unauthorized transactions.

“Major desktop banking trojans have long abandoned the consumer banking realms for bigger bounties in BEC fraud, ransomware attacks and high-value individual heists,” Tavor said. “This, together with the ongoing trend of online banking transitioning to mobile, caused a void in the underground cybercrime arena to be filled by mobile banking malware.”