There’s no immediately obvious answer when you ask someone what the first Neal Adams work is that jumps to mind. Is it “The Joker’s Five Way Revenge?” Green Lantern/Green Arrow: Hard Traveling Heroes? The batshit, hairy-chested insanity of Batman: Odyssey? Late Silver Age X-Men? We could spend a thousand words listing the comics he drew for 50 years and still only barely scrape the surface of the man’s contributions to comic art.

And none of that comes close to his impact behind the scenes. Adams, who died last week at the age of 80, was a titan on the page, but he was also one of the first big name creators to pick a fight with Marvel and Warner Brothers and win. And when he beat Warner, it was one of the biggest fights ever. And the prize was no less than Superman.

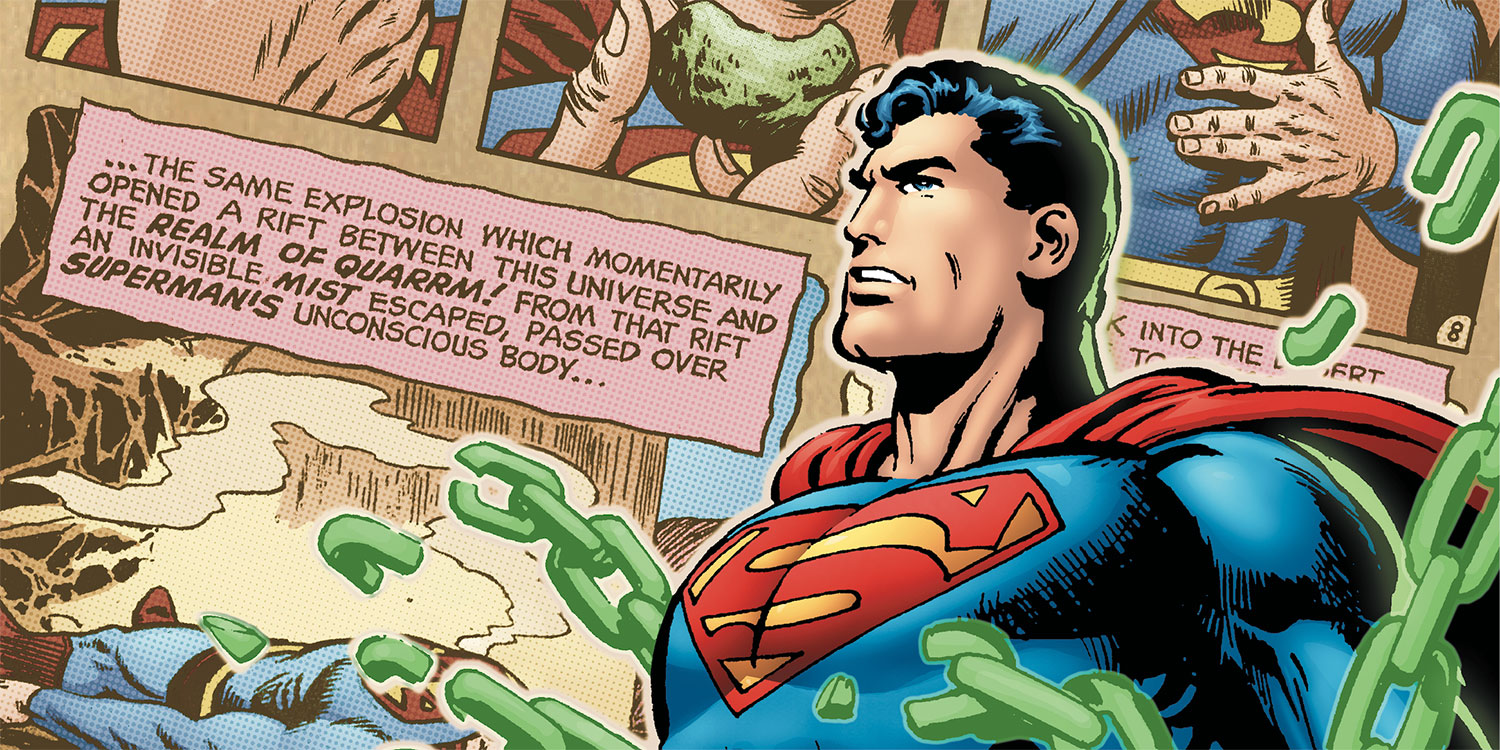

Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster were two regular guys from modest Cleveland backgrounds who met in high school and went on to create the most important superhero in comics history: Superman. And when they did in the 1930s, even with radio shows and movie serials being a going concern, nobody had the slightest inkling what Superman or superheroes would become. So when they sold the rights to DC Comics, the company publishing his stories at the time, for $130 (about $2500 in today’s dollars), it was a reasonable business deal.

And then the next 40 years happened. Siegel and Shuster earned money writing Superman comics, but DC allegedly used an old Superboy pitch as the basis for a published story and got sketchy about royalties from the radio show, so the pair sued DC for their copyright back and lost.

The duo never again had the same success they did in Metropolis, despite chasing it for as long as they could make comics. They sued again in the late ‘60s and Siegel was effectively blacklisted because of it, losing all DC work ahead of the lawsuit and never regaining it (Shuster was more or less blind at this point, and completely out of the comics game). The two suffered from financial problems for most of the later period of their lives.

Adams was an established, capital letters Big Deal by the mid 1970s, having already revolutionized Green Lantern and brought Batman into the future. Ahead of production on the first Superman movie, Adams got a letter from Siegel outlining their plight, and he was outraged. Together with Joker creator Jerry Robinson, they brought Siegel and Shuster to New York, put them up in a hotel, and brought the Superman creators around for a bit of a press tour designed to shame Warner into supporting the nearly destitute Superman creators.

It worked. Warner agreed to pay Siegel and Shuster a $20,000 a year pension. Adams and Robinson successfully shamed Warner Brothers into paying Superman’s creators something. It wasn’t commensurate with the company’s profits from Superman, but it was a win in an industry where those don’t come often for creators, especially at the time.

Case in point: original artwork. Standard practice in the comics industry now is to return original artwork to the artists, with pages being split between pencilers and inkers, giving those artists some extra money on the secondary collector’s market (if there’s originals to return and the artist isn’t working all digital, but that’s a creator’s rights article for another time). But it wasn’t always that way. The practice of returning original art to the people who made it wasn’t industry standard until the mid-1970s. This meant DECADES of original art was filed away in DC and Marvel offices (or on a stool near an elevator in Marvel offices, or destroyed entirely in many cases) and had to be returned to creators. DC was apparently pretty diligent about it, but Marvel took their time, and following a change in copyright law in the late ‘70s, they started including a release form that granted Marvel the rights to their creations.

But the form they offered to Jack Kirby was flat out ridiculous. It assigned all the rights to everything Kirby created at Marvel to the company, but it also forbade him from selling or even displaying any of his original art. Marvel apparently wanted to still own his original pages, but was graciously willing to let him store it in his Long Island home until they wanted to use it for something.

Adams, already not a fan of the release forms, was incensed by Marvel’s treatment of Kirby. He joined with a chorus of big name comics creators like Frank Miller and Gary Trudeau to again try and shame a big comic company into treating an artist with some shred of dignity. It wasn’t as effective as the campaign for Siegel and Shuster had been, but it did still end with success: after years of scrambling denials and failed attempts at face saving, Marvel gave Kirby an amended release to sign that gave Jack much of what he was looking for, and returned 1900 pages of original art. It only worked out to about a quarter of his total Marvel output, but it was still a significant sum at the time.

Adams was enormously important to the look of the comics we read today. But he is even more important to the creators making them, and he should be honored forever for his work to make the industry better for his peers.