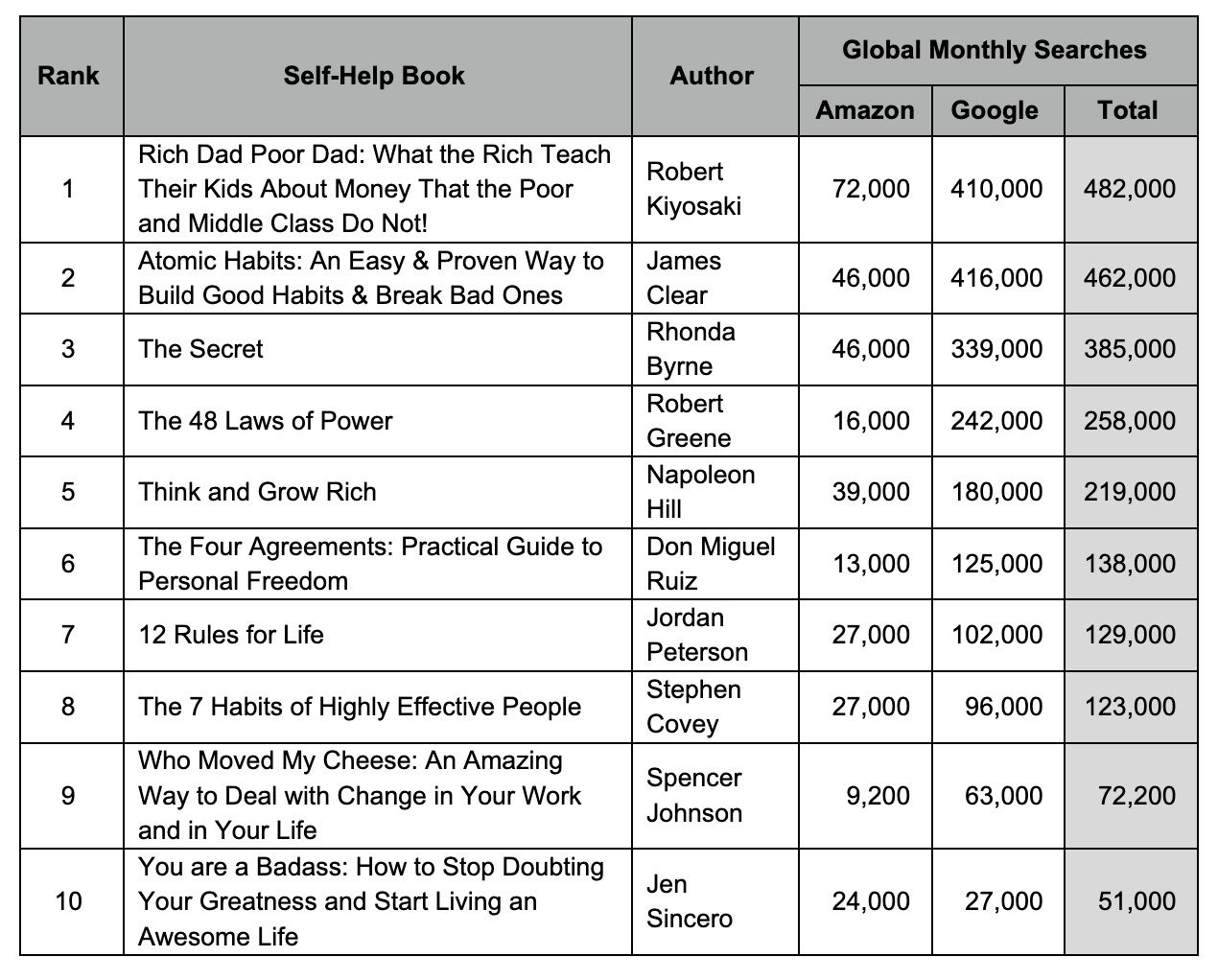

A new research study by Typing.com — a company that teaches keyboarding, digital literacy, and coding — explored the estimated monthly search volumes on Google and Amazon for the 50 most well-known self-help books. The aim was to determine which self-help titles were the most popular, and the results showcase a wide range of interests within the broad “self-help” category.

The most popular self-help books, as assessed by monthly search traffic, is a mix of some expected titles, some perennial bestsellers, and some titles that have gained notoriety within various circles (The Secret and The Four Agreements, for example, land on lists for those with an interest in spirituality; Who Moved My Cheese and 7 Habits of Highly Effective People are classics in the business world and readily accessible at airports; Jordan Peterson remains a staple among “men’s rights” “activists”).

Of the ten books, only two are by women. Few are by authors of color.

It’d be easy to criticize the most searched books on these criteria alone. Instead, it’s also worth considering the content within these books.

In July 2020, writer Devi Abraham shared her experiences reading two popular self-help titles. The first, Atomic Habits, is included in the above list. The second, Cal Newport’s Deep Work, is not on the most popular list above but is a title cited regularly as a must-read for better productivity.

Not only are men the most popular writers of self-help books, but they are their own subjects as well. Self-help is not an all-white category, and it continues to grow more diverse annually; this is positive not only because self-help books are big business — and have their own New York Times Best Seller List — but it’s positive because the white male subject is not, nor should it be, the standard way of operating.

Unfortunately, it is built into the very bones of helping itself.

Self-help books have been around for centuries, but it wasn’t until the 1960s where they became a popular genre within the reading public. This was, in addition to a time where capitalism grew and afforded (white, middle class) individuals the time and money to buy, read, and write such books, when helping professions became more common and legitimized. This was also the era when the psychology professions such as counseling and social work became more accessible. The 1950s and ’60s in particular brought about the development of early cognitive behavioral therapy (thanks to Albert Ellis) and the person-centered therapy of Carl Rogers.

Rogers is widely regarded as a groundbreaker in the field of therapy. His work, which centered on people as unique and capable individuals, moved helping away from Freudian psychoanalysis and the sometimes-problematic fixations of that theory (n.b., psychoanalysis has contemporary uses still!). Rogers was a humanist who saw people in an optimistic light and believed every individual had the capacity to grow, change, and develop into who it is they want to be. He believed every individual could self-actualize.

But as much as Rogers did for the helping fields, he followed in the steps of his predecessors: white men. He worked in an area of rigid gender stereotypes and though empathy, unconditional positive regard, and presence with clients were key to his theory of helping, his own thinking was still inspired by his lived experience in a patriarchal society. It was Rogers’s daughter, Natalie, who challenged her father to think bigger and consider the perspective from which his helping came. Natalie expanded upon her father’s work, growing an entire field of person-centered therapy of her own with expressive arts, and her first book, Emerging Women, was one that highlighted how much of the roles women “traditionally” took were no longer the roles women were taking.

Her work, and the work of dozens of other women in the helping field, have had no less impact than their male forerunners and contemporaries. But as is the case today, women’s voices — and women’s lives — are curiously absent from most popular and most sought self-help books.

Self-help/self-improvement books have always had their fans and their critics and rightly so. But they came of age in a rapidly moving world grounded in capitalism, and the promise of a fix packaged into a neat, easy-to-read book made them prime for sales — and big ones. These books are broadly defined, and they shift in their tone, their content, and their approach in much the same way therapy does. If one book doesn’t work, maybe the next one will. Unlike therapy, though, there is no end goal for no longer needing the next self-help book; the more, the better, the closer to actualization.

With a foundation created by white men, no matter how groundbreaking their work and no matter how inclusive it may strive be, it should come as no surprise that self-help continues to be an arena for, by, and centering men. Five pages of addressing women’s issues in two of the top books is, frankly, surprising in scope. Men have had — and continue to have — a day that requires less unpaid labor than female counterparts.*

Because men do not need to think about the hours of unpaid labor, the invisible work, the countless time spent making grocery-meal-schoolbag checklists, they do not have the lived experience of needing to use these realities for fodder. They have the privilege of writing for an uninterrupted hour and not answering their phone or email.^ They do not need to schedule their days around school pickups or drop offs, playdates or trips to the post office. They are not often tasked with finding caregivers, being primary caregiver, or doing both; this task is especially burdensome to women of color, particularly if they themselves work as caregivers, as Angela Garbes explores in Essential Labor.

Men do not think about it because they don’t see it, and they don’t see it because they do not have to see it. Taken as a collective, our dedication to self-help books and the popularity of those by men, once again reiterate the role self-help books play for us. Where these men say we can pull up our bootstraps and solve our problems, they miss the bigger picture. There are not individual solutions to collective problems and worse, by framing problems in the context of male-driven solutions, we grow a market for more self-help books to solve the same problems that will not be solved away through self-help books penned by men.

Over decades of reading self-help books, both for fun and for my own growth, I’ve learned the true value of this category isn’t in what you find tucked between the pages. It’s instead precisely what isn’t seen: the blank spaces and the questioning of why it is we need to improve ourselves as individuals, rather than push back against the systems that force such feelings of inadequacy and experiences of disenfranchisement upon us.

For white men, this is rarely a pursuit they need to question. They built the system. Women missing from the pages and the searches is on purpose. If they’re not seen, why then, would they need to improve or self-actualize?

“We can’t become the best versions of ourselves — no matter what that looks like — without ensuring our neighbor can do the same. That development doesn’t happen over the course of reading a book. The time and energy is a privilege afforded to few,” I wrote in a previous musing on self-help. “Becoming one’s best self only happens when we take what we see or don’t see in the book and put ourselves to work in our communities, with those whose needs we can help meet through hard work, through hard listening, and when we hand over the mic to those whose voices have too often been ignored, spoken over, or silenced all together.”

Men, particularly white men, still have a lot of work to do.

Perhaps this is partially why there is some worry in the self-help world that the market will begin to crumble. The bread and butter experts and consumers are baby boomers, 60 or older. There are few millennials making a name for themselves in self-development and fewer still in gen z.

Except there are experts in both of these generations. There are dozens of self-help books and self-development books that aim to bring solutions and empowerment to younger adults. These books tackle complex, nuanced topics including community and friendship (How We Show Up and Big Friendship), self-confidence and anxiety (Why Has Nobody Told Me This Before?, How To Be Yourself, Brave Not Perfect, The Body Is Not an Apology), sex (Come as You Are), and motherhood/care-taking (Like A Mother and Essential Labor).

They’re just not by or about white men.

They’re about dismantling the patriarchal systems, not tying tighter knots around them.

*Of course this is not universal and it is based on a gender binary. We know this. That doesn’t change the cultural perception that this is what is seen and valued.

^A white man once told me how royally offended he was I use an out of office responder outlining my response times for my personal email because of how unprofessional that was. Amazing how a woman laying claim to her boundaries is an offense.