Children’s verse offers the opportunity to normalize children’s taboo feelings, urges, and actions. This approach means acting as a reaction to didactic traditions and the society’s pressure to “be good.” By “didactic,” I mean literature that is instructional, offering guidance, in particular of morals, values, and what’s deemed “good” as opposed to “unsavory.” Much of the earliest history of children’s literature is didactic. It took a radical nonconformist, like poet Shel Silverstein, to upend the didactic era and scratch the “id” of children everywhere, inviting them to tease out their “inappropriate” inclinations. Silverstein’s subversive children’s verse uses poetry as a vehicle to inflict moral chaos, chasing kid lit out of the didactic and into pure, silly fun.

Through careful craft choices on the language and thematic level, writers of children’s verse can harness language, form, and theme in tandem to subvert didacticism and explore mischievous “id” desires in the safe space of a book. When I talk about the “id,” I’m referring to the part of ourselves that, according to Freud, is subconsciously drawn to base urges and desires, to inappropriate desires and impulses. The craft decisions made by Shel Silverstein encourage young readers to explore their id, to get in touch with their bad side, effectively normalizing wicked urges as a response to the didactic movement.

Shel Silverstein’s Where the Sidewalk Ends, a 1974 compilation of the writer’s poems and drawings, is a landmark work of children’s verse. In dozens of poems encompassing a wide range of forms, Silverstein describes and encourages mischievous behavior. Lest any reader think they are not the ideal audience for poems — perhaps, in thinking they are not “good” enough for poetry — Silverstein’s “Invitation” opens the book by inviting all kinds of readers inside. Silverstein specifies that not just obedient “pray-er” readers are welcome, but “liar” and “pretender” readers, too.

Several poems feature these liars and pretenders, too, such as “Smart,” in which a clever and scheming child takes the one-dollar bill his father rewards him with for being “his smartest son” and trades up for five pennies through outright deception and taking advantage of others’ weaknesses, including a blind man and another who is a “fool.” The joke’s on the boy, though, who is supposed to be smart but is not smart enough to realize that he ended up trading away a dollar for a worse deal, no matter that five pennies feels bigger than one dollar bill.

In “Sick,” Peggy Ann McKay lists a host of reasons why she is too sick to go to school, ranging from major bodily injuries to systemic malfunctions and nasty, possibly fatal infections, such as “I have the measles and the mumps, / A gash, a rash, and purple bumps / My mouth is wet, my throat is dry, / I’m going blind in my right eye. / My tonsils are as big as rocks, / I’ve counted sixteen chicken pox / And there’s one more—that’s seventeen.” But when Peggy Ann learns that it is actually a weekend day, she remarks: “What’s that? What’s that you say? / You say today is… Saturday? / G’bye, I’m going out to play!”

Silverstein takes a common child’s lie about being too sick for school, exaggerates the symptoms in a hyperbolic list, and then ends with the relatable joy of dropping the ruse because it is a weekend and school is avoided. Through poetry and in particular the language device of hyperbole, Silverstein reflects a mirror to the world of a child’s instinct to lie and deceive to avoid something unpleasant while leaving out the judgment. A hallmark of Silverstein’s mischievous poetry is to refrain from judging children for their transgressions, with the exception of Silverstein’s rather obvious disdain for kids who get sucked into watching television (see “Jimmy Jet and His TV Set”).

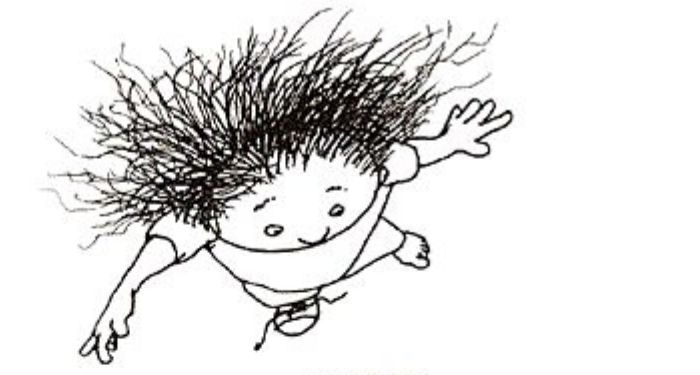

Another way Silverstein uses language to encourage mischief and bad behavior is through strategic formatting. The poem “Lazy Jane” is written as a list, one word per line, that descends into the mouth of an illustrated thirsty child who wants a glass of water but will wait for it to rain and drop into her mouth. Through clever use of vertical formatting, Silverstein’s language is arranged to mimic the action of water dropping into Jane’s mouth, a slow and unlikely process. At the same time, Silverstein uses repetition to drive his point home. The poem opens by identifying “Lazy / lazy / lazy / lazy / lazy / lazy / Jane” as someone too “lazy” to get up and get herself a glass of water (87). The poem’s structure mocks Jane, who is introduced to us as “lazy” six times before we get her name. Later in the poem, Silverstein writes: “so / she / waits / and / waits / and / waits / and / waits / and / waits / for / it / to / rain.” The repeated “lazy” words, along with the “and / waits” refrain, create a rhythm that complements Jane’s own lackadaisical behavior. “Lazy Jane” pokes fun at its heroine, but again, Silverstein refrains from judging Jane.

The children Silverstein writes for and about are liars and pretenders, indeed. Silverstein’s craft releases poetry from the didactic tradition filled with lessons on morals, societal do’s and do-not’s, and ethics. In fact, one could read Silverstein’s poetry as an intentional normalization of the taboo urge and a child’s id instinct. His work contains a counter-didactic instruction that rejects shaming culture and accepts rather than represses one’s curiosities. Silverstein’s clever use of linguistic devices and strategies reinforces the thematic material, showing how poetry offers a great tool to break open language — and stuffy rule books at the same time.