An interest rate rise from the European Central Bank (ECB), its first for 11 years, was always nailed on.

Christine Lagarde, the ECB’s president, had already explicitly stated in June that the bank would be increasing its main policy rate by a 0.25 percentage points this month.

But the decision took on much greater significance when, on Tuesday this week, Reuters reported – citing two sources “with direct knowledge of the debate” – that the bank’s governing council would discuss a possible increase of 0.5 percentage points.

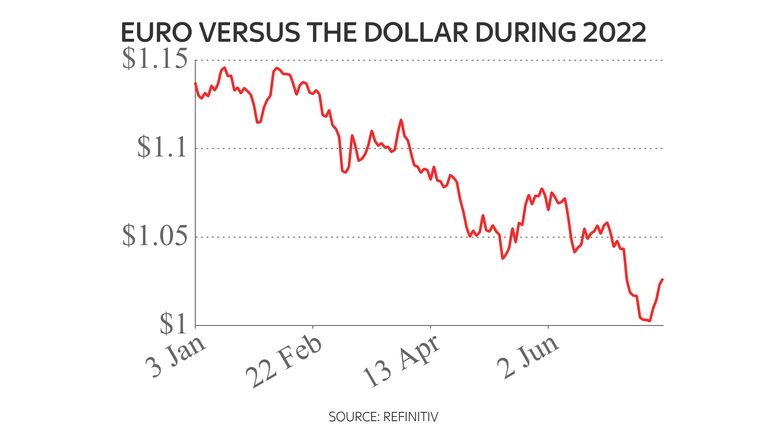

The euro surged by more than 1% against the US dollar on that news, which came just days after the single currency had fallen to below parity against the greenback for the first time in nearly 20 years.

So the only real issue was whether the ECB would raise by 25 or 50 basis points – and today it went for the latter.

It is a big, dramatic move from the ECB, which had not moved interest rates since September 2019, when it cut its main policy rate from -0.4% to -0.5%.

So interest rates in the eurozone are no longer negative for the first time in nearly three years. It reflects mounting concern across the eurozone over burgeoning inflation. Even after the Reuters report, most economists still expected only a quarter point rise. The euro rose by nearly 1% against the dollar immediately after the news.

In reality, the ECB really had very little choice. The bank, like the Bank of England, is mandated to target an inflation rate of 2% but inflationary pressures have been building up in the euro zone since the start of the year.

Consumer price inflation in the eurozone hit 8.6% in June, up from 8.1% in May, but in some eurozone countries it is already higher than that. For example, in Greece it is 12%, in Belgium it is 10.5%, in Spain it is 10% and in the Netherlands it is 9.9%.

In the Baltic states of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia that border Russia, the rates are 19%, 20.5% and 22% respectively.

Inflation is set to increase further in coming months – producer price inflation, a good indication of where consumer price inflation is heading next, hit 32% in Germany, the eurozone’s biggest and most important member, last month.

Explaining the move, the bank said: “The governing council judged that it is appropriate to take a larger first step on its policy rate normalisation path than signalled at its previous meeting. This decision is based on the governing council’s updated assessment of inflation risks… it will support the return of inflation to the governing council’s medium-term target by strengthening the anchoring of inflation expectations and by ensuring that demand conditions adjust to deliver its inflation target in the medium term.”

The other key point of interest was whether the ECB would launch a so-called anti fragmentation tool, in the jargon.

This is a measure aimed at tackling the way that members of the eurozone have been seeing differences in their implied borrowing costs as the economic outlook deteriorates.

Investors in government bonds issued by countries perceived to be risky, such as Italy, have been demanding a premium for holding them over bonds issued by countries, like Germany, deemed less risky.

For example, the yield (or implied borrowing cost) on 10-year Italian government bonds today hit 3.7% at one point, compared with the yield of just 1.235% on 10-year German government bonds.

This has brought back memories of the eurozone debt crisis a decade ago that, at one point, threatened to overwhelm the finances of eurozone members such as Spain, Portugal, Italy, Ireland and Greece – and which prompted the ECB to launch a massive package of asset purchases (quantitative easing in the jargon).

The move prevented the euro from breaking apart. More recently, the ECB has relaunched asset purchases in response to the pandemic, but has since announced plans to halt the scheme. It is that news which has sparked these moves in government bonds – and explains the talk of an anti-fragmentation tool.

It was essentially seen as a way of enabling the ECB to carry on raising interest rates, in response to the take-off in inflation, without feeling inhibited by the need to prevent wider divergence between eurozone government bond yields.

This has become even more critical in the wake of Thursday morning’s resignation of Mario Draghi, Ms Lagarde’s predecessor at the ECB, as prime minister of Italy.

The ECB duly announced that it would be introducing an anti-fragmentation tool, which it called the transmission protection instrument (TPI).

It added: “The TPI will be an addition to the governing council’s toolkit and can be activated to counter unwarranted, disorderly market dynamics that pose a serious threat to the transmission of monetary policy across the euro area.

“The scale of TPI purchases depends on the severity of the risks facing policy transmission…by safeguarding the transmission mechanism, the TPI will allow the governing council to more effectively deliver on its price stability mandate.”

The big question is whether these measures will be enough to keep inflation in the eurozone at bay and particularly in an environment in which energy prices will continue to remain at elevated levels and in which the EU is urging all member states to reduce their gas consumption by 15% – the equivalent of six weeks consumption.

Most economists and market watchers are certainly expecting further interest rate hikes in coming months.

Gurpreet Gill, macro strategist, global fixed income, at Goldman Sachs Asset Management, said: “With inflation running above 10% in nine eurozone economies, a level expected to be exceeded across the region in September and wage growth accelerating to decade highs, it is likely the ECB will deliver another 0.5% hike at its September meeting.

“Given the delicate balancing act the governing council faces due to the threat of weakening demand however, we anticipate two further less aggressive rate hikes of 0.25% in November and December.”

The problem the ECB has resembles the dilemma facing the Bank of England – it is caught between raising interest rates so timidly that it guarantees further inflation and doing so in such an aggressive way that it tips the economy into a recession.

Seema Shah, chief strategist at the asset manager Principal Global Investors, said: “The ECB’s era of negative rates has finally come to an end, and with quite a bang – but it’s not against a backdrop of strong economic growth and certainly not accompanied by celebratory smiles.

“Quite the contrary. The ECB is hiking into a drastically slowing economy, facing a severe stagflationary shock that is quite beyond its control, while also facing an Italian political crisis which presents a difficult sovereign risk dilemma.

“There is no other developed market central bank in a worse position than the ECB.”

Today’s move by the ECB may also force the Bank of England itself to be more aggressive. It has to date raised its main policy rate in five consecutive meetings in a sequence that began just before Christmas last year – taking Bank rate from 0.1% to 1.25% – but only in small increments of no more than a 0.25 percentage points at a time.

Yet other central banks around the world have been raising interest rates in a more aggressive manner. The US Federal Reserve raised interest rates by 0.75 percentage points last month and is widely expected to do at least that again next week.

The central banks of Australia, New Zealand and South Korea all raised interest rates by 0.5 percentage points last week while the Bank of Canada went further still and raised interest rates by a full percentage point.

The boldness of the ECB today may leave the Bank’s Monetary Policy Committee concluding that it will have to raise interest rates by at least 0.5 percentage points when it next meets on 4 August.

An increase in Bank Rate from 1.25% to 1.75% that day is now the way to bet.