While there are dozens of “back when we were in school” memories shared online and across social media, the comments on posts like this one are full of people wondering how so many people across the world had the same exact things. And that’s something I can’t stop thinking about either. Why did so many other people my age have memories associated with a student planner?

The answer is fascinating.

American Education in the 1980s

The 1980s were a significant time of education reform in America.

At the start of the decade, Ronald Reagan appointed Terrel Bell as Secretary of Education. Bell’s role was supposed to be overseeing the dismantling of the Department of Education—sound familiar?—but he ran into several hurdles. In 1981, Bell approached Reagan with another idea: could they create a commission to study American education and put together a report with their findings?

It was not unprecedented, as such commissions had happened in the past, and Reagan gave the green light. Over the next several years, a commission of 12 administrators, 1 businessperson, 1 chemist, 1 physicist, 1 politician, 1 conservative activist, and 1 teacher, worked on what would become the 1983 report A Nation at Risk.

The report pushed for an overhaul of education, and much of the language in the report mirrors what we’re hearing right now across the country related to education. We’re a nation of poorly educated young people failing to meet the needs of a global world. There was an emphasis on how America has lost its way in terms of the purpose of school. Because schools became too invested in “personal, social, and political problems,” the institutions were failing to do their job of educating. Schools were wasting time and money on issues that were to be addressed in the home with the parents. (Sigh).

The educational foundations of our society are presently being eroded by a rising tide of mediocrity that threatens our very future as a Nation and a people — from A Nation at Risk

Even though the commission’s report led to reform for education, the report itself was not well received. This was particularly true for, well, those who actually worked in education (recall the commission, despite its focus on high school education, had a whopping one educator on it). A group out of New Mexico took a critical look at A Nation at Risk with their Sandia Report. That report went mostly unnoticed, which was convenient for Reagan-era politicians since the data in Sandia directly contradicted that in their own commission. Student SAT scores had not, in fact, declined substantially in the 1970s. In fact, they rose—but a more diverse demographic of students were taking the SAT in the late ’70s compared to the early ’70s. Facts and data mattered in the ’80s Reagan era as much as they do now.

A Nation at Risk ultimately flipped Reagan’s initial goals of getting rid of the Department of Education. It instead spurred a movement pushing for a more rigorous set of standards students needed to meet. The report used war-coded language during the heights of the Cold War, and it pointed to how, under liberal leadership, public education had withered into little more than social-emotional learning (in the ’80s, they called it “self-esteem learning”).

All of this occurred in an era before the ready availability of the internet and social media, so the average person got this information via newspapers. And just like now, much of the news about education and A Nation At Risk was not especially critical. As Tamim Ansary notes, The Washington Post alone ran more than 24 stories about the report.

Educational stakes rose in the Reagan era, and George H. W. Bush continued to push a reform agenda when he took office. There’s a whole lot to unpack about the ’80s and how they mirror contemporary education beliefs being espoused by the grown adults whose own education was impacted by the reforms implemented based on political agenda, rather than research. What’s important to take away is that educators and students were rarely part of the conversation.

A Story of a Kitchen Table Business

Prior to about 1985, when students went to school, they did not carry planners or agendas. They were not required school supplies. But as the stakes in education were increasing, so, too, was the pressure on educators and students to keep track of increasingly complex assignments. Reagan-era reform tied student performance to educators, meaning that if students were not universally scoring well on tests and/or showcasing more rigor in their knowledge and studies, then the educators themselves were to blame and suffered the consequences.

Homework increased in quantity in the 1980s after several decades of decline. Although data from the National Assessment of Education Progress in this Brookings Report showcases an increase in homework from 1984 to 2012, that data from 1984 is interesting. Most nine-year-olds and nearly all 13- and 17-year-old students had homework on any given night.

So how were these students—and subsequently their teachers—supposed to keep up?

Enter Sharon Powers.

Sitting at her kitchen table in 1985, Sharon began to design an agenda book. It was for Central Catholic Junior/Senior High School in Lafayette, Indiana, where her son attended. Once she created the planner, dubbed the Knightline, Powers realized she’d done something pretty unique and immediately created prototypes of a similar agenda for several other local schools. There was the West Lafayette Docket, the Harrison High School Barn Door, the McCutcheon High School Maveranda, and the Lafayette Jefferson High School Broncho Board. Powers found herself a market and officially launched her School Datebooks business in Lafayette, Indiana.

No one had yet considered the potential market for agendas in schools across the country, but 1985 could not have been more prime. Company lore has it that Powers was inspired to create the datebook because of her own son, Tim, who after college, came back to Lafayette to help run the business.* As the success of School Datebooks grew, the company itself expanded to meet more market needs. All of these products were folded into a larger company called SDI Innovations, but School Datebooks remains their flagship product.

As of the 2019-2020 school year, School Datebooks reached over 13,000 schools. There are approximately 115,170 schools across the US, so School Datebooks entered 11% of the total US school population. Tim Powers, in an interview with the Hanover College alumni magazine, noted that School Datebooks saw 20-40% growth each year in the late ’90s.

Eleven percent of the US school population is impressive, but it’s not enough for an image of a school agenda to unlock core memories for such a huge amount of the internet. Especially when many of those commenting about their DJ skills on the cover or their requirement to get the planner signed by a parent or guardian every week came from Canadians.

That’s because the story of the kitchen table agenda isn’t alone. Just a couple of years earlier, a different company launched a datebook product that would enter school districts first in Canada and then the US.

A Canadian Company Did It First

Premier Agendas doesn’t have as quaint a kitchen table origin as School Datebooks, though it, too, started humbly. In 1983, a small print shop in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada realized that there was no easily accessible, inexpensive, and widespread agenda book specifically designed for school students. Premier Printing Ltd. tested out a planner that could be customized by school districts across several provinces and found the response encouraging.

Over the 1980s, the Premier Agendas spread across Canada and it became clear that there was also a market in the US. They expanded, selling their Premier Agendas in the US. They reached a total of 5 million North American students by 1990. Initially very basic, Premier Agenda saw their success growing by creating agendas that appealed to their young audience. They incorporated study tips, quotes and advice, and other fun details that contributed to student social emotional learning started around 1995. By 2010, the company boasted that 17 million students across North America were using Premier Planners.

Premier Agendas changed ownership several times, but its US operations were based in Bellingham, Washington, beginning in 1994. Premier Agendas was acquired by School Specialty, Inc., in December 2001, and by then were the largest provider of academic agendas in the US and Canada. In the US alone, Premier Agendas supplied their goods to 15,000 schools (or 13% of all US schools).

Now, For a Twist

So here’s where the story of two planners embedded in the memories of nearly half of North American adults takes a twist.

Premier Agendas’s reach was wider than School Datebooks’ and began a couple of years before them. Sharon Powers likely had no idea there was a competitor in the market, given that there was no internet or easily accessible database of businesses across the globe—none of her local schools had been sold products like a student agenda before she sold her own. Both businesses grew substantially, despite humble beginnings in each, thanks in part to an era of increased panic over education.

But the market would change in the late 2010s.

In 2019, Premier Agendas announced they would be shutting down the business. The Bellingham facility would remain open, but it would no longer have an Agendas division. It’s likely that a lot of this had to do with the fact students no longer have a need for paper agendas the way they did in the ’80s, ’90s, ’00s, and even just a few years earlier. More and more was done digitally or in planners acquired by students themselves—if you’re anything like me, you’re also sucked into nonstop planner/agenda setup videos on YouTube and TikTok and convinced this time that you’ll stick to it. It would be prudent to mention here this was also an era of school budget cuts and despite how little the planners cost, it was an easy line to cross out to save a few hundred dollars per year.**

It looked like Premier Agendas would quietly disappear and with it, dozens of full time jobs. Several employees would be able to stay on in sales roles and others would be offered roles elsewhere in the company, but their work would no longer be needed in the Agenda side of the business.

That is, until SDI Innovations, which owns School Datebooks, acquired Premier Agendas in 2020.

No longer competitors, Premier Agendas was folded into School Datebooks, giving them a reach of over 15,000 today.

There’s no way to accurately capture how many US and Canadian students had either Premier Planners or School Datebooks, but a rough estimate would put the combined reach of both somewhere over one-third and up to one-half of students in North America. That’s tremendous scale and reach for any product, and that neither business used it as a way to advertise themselves directly to their audience is pretty impressive. These agendas are a memory that connected so many thousands of those who were students between the 1980s and early 2010s. They were a staple, even if what seemed to be one universal datebook was actually two slightly different ones.

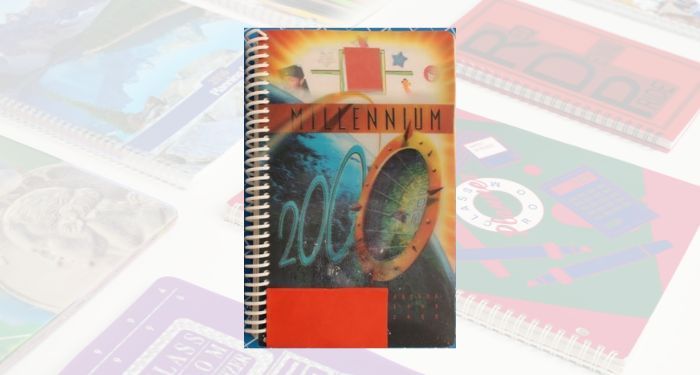

The planner at the top of this piece? That was from Premier Agenda, also known as the one in more schools in North America. You can peep this version, as well as one of the Canadian versions.

Perhaps the image below, among some of those made by School Datebooks, sparks a memory.

School Datebooks Today

I reached out to the School Datebook team to see if they’d share one of their early cover renditions and not only were they excited to, we actually got on a phone call to talk. During our conversation, I learned some interesting things. First, this year celebrates 40 years in the datebook business, which is no small feat. But perhaps even more interesting for People Of A Certain Age, this year marks the 25th anniversary of the famous Millennium planner (Premier Agenda’s Version). Rumor has it that there might be some exciting announcements in honor of these milestones in the near future.

Interesting to me and perhaps less so to a general readership? School Datebooks provided the planners of my middle school experience. What should not be surprising is that the distribution of the planners had some regional ties—my suburban Chicago schools went with School Datebooks, likely because SDI Innovations was in Indiana.

The team at School Datebooks has been fun to see pop up in those nostalgic posts on TikTok and Instagram. They’ve put a lot of energy into social media over the last year, eager to tie the origin story at Sharon Powers’s kitchen table to the Premier Planners that drive so many memories because they are now one in the same. It’s not too often you see brands engage with these kinds of posts, and more, it’s rare you see it done in a way that’s fun and educational (without being a pitch for the product—which, well, they’ve been good at since the start!).

Sadly, Sharon Powers passed away in November 2023, but her memory will live on across North American schools for a long, long time. Indeed, it lives on every time one of these social media or Reddit posts pops up.

That’s a heck of a legacy.

School Datebooks sells several styles of planners on Amazon if you’re itching for one. Know that while they’re cute and functional, they will not let you live out our DJ dreams via vinyl-esque covers today…yet, at least. Perhaps that’ll be something millennials get to revisit in a future product!

Find more posts like this via our subscription publication, The Deep Dive! Weekly staff-written articles are available free of charge, or you can sign up for a paid subscription to get additional content and access to community features.

*This company lore was debunked by a member of the SDI Innovations team on our phone call—but it’s a fun one, isn’t it?

**If you’re curious, it looks like the cost of these agendas in the 2022-2023 school year ranged anywhere from $4 to $15 a student, depending on school discounts and customization. Not bad!